The following is a translation of an article by Otto Janka that appeared in the original Czech in "Český Merán", a limited circulation periodical published in 2003.

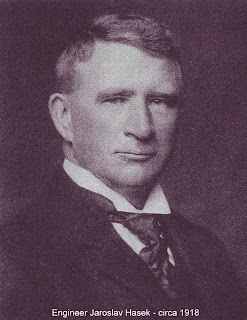

The following is a translation of an article by Otto Janka that appeared in the original Czech in "Český Merán", a limited circulation periodical published in 2003.His life was a reflection of his times. He began in “certified poverty”, as documented by the municipal office in Vysoké nad Jizerou on September 26th, 1893. He ended his days with another version of “certified poverty”. He was expropriated by the communist regional national council in Sedlčany on May 18, 1952, and the following year his pension was cut by 83%.

In the intervening time between his first and second “certification of poverty”, Jaroslav Hásek experienced a life of exceptional talent, exceptional success, and indeed exceptional wealth.

He was born in 1874 as the eleventh child of a gingerbread baker in Vysoké nad Jizerou. Aside from the implements for making honey marzipan, they also owned a field and a small house. There was not much to the field, and when Jaroslav Hásek's father died in 1884, they began to borrow money against the property. At the time when Jaroslav Hásek received his first “certification of poverty” the family had almost only debts, and the field was long gone.

Much later, already as a seasoned builder and owner of a manor and estate in Prčice, he began to compile his autobiography. But perhaps he did that even later. According to his daughter, it was only after he received his second “certification of poverty”; when he was, as at the inception of his story, once again hopelessly poor.

He was a engineer, and if he could have created his memoirs at a drafting table they would have meant more to him. But it was not long before he lost interest in writing them. He only reached the beginning of the sixteenth page when he abandoned the effort. Years later they were discovered by his grandson Daniel, and thus they were preserved.

Some incidents from his childhood, which Jaroslav Hásek related in his memoirs, substantially illustrate that he was purposeful, constant, tenacious, and that when he decided on an objective he pursued it without regard for obstacles that were placed in his way. He was four years old when he received his first pair of pants. He was only allowed to wear them on Sunday. On Monday, once more, he was given a skirt handed down from his older sister, bound with chord. But he determined he would no longer go about in a skirt. After all, he was already four years old. So he went out in front of the house and rolled around in the first puddle that he saw. He returned home. He was told off, and they changed him into a different skirt, handed down from another older sister. He went out and rolled around in the puddle again. He came home and was beaten. He was changed into yet another skirt bound with a chord. He went out and rolled in the puddle. He was beaten even more. And so on. So when his mother ran out of skirts handed down from his sisters, she finally gave him the pants.

When he started going to school a new grading system was introduced with five as the new and absolute worst grade. Learning did not interest him. So he soon found out that if he didn't go to school, he could go somewhere else, and all too frequently he wanted to go somewhere other than school. So his report card gathered a significant collection of the new fives.

His older brother Bohuslav was already at that time a teacher in a village one room school in Tuhan', and he decided that he would take his little brother along and teach him how to study. The plan was carried out, and eventually with such outstanding results that in only a year Bohuslav took his little brother to the principal of the municipal school in Lomnice to see if he would accept him among his pupils.

“No, I can't” the principal answered them. “He is not yet ten, and it would be against the law.” They were already leaving, when the principal called out a sentence which Jaroslav was to remember for the rest of his life. “Wait, colleague, since you are already here, I shall at least test the boy.” The Principal tested Jaroslav in all subjects. At length. Intensively. And then the sound of a second sentence which Jaroslav Hásek put in quotations many years later. “In spite of flouting the regulations, I shall arrange it, so the boy can attend our municipal school.”

At the municipal school Jaroslav Hásek was so far ahead of the rest, that the gap between him and the second best pupil was huge. He became the most frequent assistant to the teacher, Mr. Jare, in chemistry and physics experiments and in natural sciences. He was a well rounded student. When he had eaten his slice of dry bread at noon, he had lots of time left over from the afternoon studies. Sometimes he played a game with the boys. Sometimes not. He would shut himself in the natural sciences study.

Later he received his last fabulous report card and prepared to go on studying. He wanted to learn to be a gardener at Mr. Mazanka's in Lomnice nad Popelkou. Actually he didn't, but he had no choice. There was no money at home for further studies.

However...he had more brothers. His oldest brother Francis was already a professor at the farm (management) school in Přerov. When he looked over Jaroslav's report card from the municipal school, he decide that he would send the little brother to Jičín, so he could study further at the secondary school.

From the memoirs of Jaroslav Hásek, which end with Jičín, it almost appears that the four years he lived in Jičín determined his life from then on. However it was not the town – which in the eyes of a country boy was surely much too big – but it was the Jičín fish pond, to which at the time and later in his memoirs that he constantly returned.

He wrote: “...Jičín always had a magnetic attraction for me, because I heard that there was a large fish pond there, and as luck would have it, later I lived in the mill on the dam that contained that pond. In winter just as in summer I would hang around in its vicinity. I learned every activity that that was related to the pond perfectly. Swimming, rowing, skating, and also...catching water bugs.

Does Jaroslav Hásek eventually go off to sea simply because the sea is a lot bigger than the Jičín pond? I don't know. He will probably have still other reasons, but it almost seems that recollections of the Jičín pond are among the reasons for the decision.

In Jičín he also first started earning on his own. The usual way. Private lessons. However he discovered another way to access funds which was somewhat unorthodox. He sold bugs. At the secondary school there were enough boys who wanted to acquire a bug collection but were too lazy to go all the way to the pond, and even then were too inept to find them there. But they had the money to buy them. Jaroslav Hásek wrote about it: “...prices were good. A simple diving beetle was a farthing, a water boatman a penny...” The best return was for ground beatles. Like a proper naturalist, in his recollections he uses their scientific name Carabidea. Some he sold for a penny and a half, some for five farthings.

Jaroslav Hásek never forgot the Jičín pond. Only...his memories grew with him. He wrote: “...once, after many long years I went in to Jičín with my family, and stood on the dam, and we were all surprised. The children because they saw before them a relatively small pond, and they started laughing at me, since in my stories I had enlarged it considerably. Even I could hardly believe my eyes...”

Already in his second year, Jaroslav Hásek started to attend Sokol in Jičín, and although this organization was simply an athletic association at the end of the nineteenth century, it was perhaps even more a of social gathering of Czech patriots. The way to Sokol once more began with the “magnetic” pond. He wrote: “...Around the pond was an iron railing, on which one could practice various routines, such as knee circles, upthrusts...and these I conscientiously practiced there”. The youth leader at the Jičín Sokol was Mr. Mendik, who had in the past competed in gymnastics at the national level, and had even competed in France, and his enthusiasm was catching. Jaroslav Hásek “caught” this bug, and subsequently always connected Sokol with dreams of a liberated destiny for his nation.

There was only a junior high school in Jičín, so after four years Jaroslav traveled to Prague so that he could continue with his studies. With his departure for Prague his memoirs end. The next almost seventy years of his life are covered in eleven lines. Writing no longer interested him. End of story.

In Prague he studied at the First Czech High School in Ječná Street. Although he was still the top student, the new school never really grew on him. Already in Jičín he had encountered an unfriendly individual staff member in the person of a priest, Father Pršala. Why is not clear. Jaroslav Hásek was actually religious, but he did not believe everything; so he did not believe, for instance, that some priest should enlighten him on the Almighty's appearance, because there's no way that the priest would know that any more than anyone else. His relationship with the Catholic faith was even in those days somewhat strained. So perhaps Father Pršala may have had some other rationale for attempting to sink Jaroslav. Only once did he succeed. In the second year he gave him a failing grade in religion and thereby spoiled his honour standing.

In Prague, it worked the same way, only the name of the priest changed. This time he was Father Ježek, and he worked most diligently at undermining Jaroslav from the moment he discovered that Hásek was a gymnast at the Sokol at Vinohrady. It was viewed with suspicion. All members of Sokol were suspect under the monarchy. “...in a spiteful way he tried to confuse me during tests, but I outsmarted him by concentrating on religion to the point that I forced him eventually to admit with a sour expression that he must grant me an excellent grade” recalled Jaroslav Hásek later. So he overcame the second priest through diligent study of the religious curriculum, but he did not come one millimeter closer to embracing the Catholic faith.

The deepest darkness in which our nation lived under the Austrian monarchy is known to us from history texts as a time of oppression and severe bondage. “Three hundred years we have suffered...” That sentence is known to almost all of us. In recent times we have returned to it with this addition: “Three hundred years we have suffered – for the the great benefit extended,” but I digress.

The end of the nineteenth century, after graduation from high school, Jaroslav Hásek began studying at university. It was, however, still a time of restricted political freedom, but at the same time a time of substantial political action. History was no longer being written by emperors and kings, or even their generals, but by inventors and industrialists. The first Czech electro technician, František Křižík, one of the founders of our industries, František Ringhoffer, and another with the same entrepreneurial daring, Sir Emil Škoda, Edison's assistant electro technician, Emil Kolben, and so on...

It was a time of men who spent nights over drafting tables and were always coming up with new ideas. Whoever had technical capability needed nothing more. Jaroslav Hásek had technical talent, but that was practically all he had when he decided that he would study engineering.

However he still had brothers: František and Bohuslav, who supported him, and once more he started private tutoring for students of lesser ability, but now for a lot more money, and he also won two scholarships. It was a time which favored talent, and Jaroslav Hásek studied with distinction. Incidentally, as well as being an outstanding student he was also an outstanding gymnast at Sokol, but that did not bother anyone particularly.

One of his scholarships was won from “His Excellency the Imperial and Royal (I & R) Minister of Spiritual and Scholarly Affairs, according to the decision of the highly regarded (I & R) Awards Body and the faculty of the (I & R) Czech Technical University, which has awarded excellent grades, which he has accomplished in all subjects of the curriculum...” The government scholarship was for forty five gold sovereigns. The second scholarship, “endowment of Emperor Ferdinand” was for one hundred and twenty gold sovereigns, with this obligation: “...in appreciation of the benevolence, which you have encountered by way of this grant, under the appropriate published regulations during daily mass, you will be required to pray the Rosary for the founder, Emperor Ferdinand II, as well as for his (I & R) Apostolic Majesty the reigning emperor, and in addition to annually attend eight extraordinary holy masses, four times annually by official edict to pray diligently and explicitly that you will in your studies achieve satisfactory advancement...” He was able to study, provide tutoring, and also to swim and row. He also practiced fencing and sport shooting. He was still a member of the gymnastic group at Sokol in Royal Vinohrady.

In 1895 he participated in the third All Sokol Congress in Prague at Letenske Field, at which forty thousand Sokol members gathered not only from “the lands of the crown of St. Wenceslas”, but also from Croatia, France, Germany, and Austria. It was a large gathering, for which Czech patriots prepared extensively, with a festive performance of the Bartered Bride at the National Theatre, and a highly charged ceremonial address by the poet J.V. Sládka and “...including the living picture in accordance with the design of brother professor Ženíšek, which incorporated an allegory of Prague presenting a wreath to the brotherhood of Sokol, with a foreground of flags inclined...”

A component of the congress included not only floor and apparatus gymnastics, but individual and team competitions and races. Jaroslav Hásek entered the individual competition. Five hundred and ninety contestants competed in high bar, parallel bars, floor exercises, rope climb, but also high and long jump and running. Jaroslav Hásek placed third best in the higher category competition and his photograph together with the two other “champions” was published in the magazine which Sokol produced upon completion of the congress.

Even before completing university, in 1895 he enlisted in the Austrian navy. He wrote his final exams as an extramural student. Why did he enlist and why navy? I don't know. One guess I have presented is that he liked large bodies of water and the largest are at sea, but perhaps his reasoning was more practical.

Although he had two brothers who sent him money to study, and he had income from tutoring and scholarships, he was still an impoverished student. He probably wore coats handed down by his older brothers, likely they were too large or a little tight, he would have had worn out collars, and certainly he lived in cheap lodgings. In the military he received a new uniform. Although Austria generally lost wars, they did so in beautiful uniforms. He was provided a decent apartment. He likely had a batman. I don't know that for sure, but it seems likely.

His first posting was in Pola, where there was a large Austrian naval base. Istria was at that time a margraviate of the Austro-Hungarian realm, and its principal town, Pola had twenty seven thousand inhabitants, comprising Croats, Slovenes, Germans and Italians. In the shipyards, and in the (I & R) arsenal there were sixteen hundred workers employed only by the navy. In the vicinity of Pola, there were laurel woods, and sometimes gales blew up from the sea and ripped large sails to shreds and snapped masts like matchsticks, but otherwise it was a pleasant climate. Also sometimes pretty warm.

Jaroslav Hásek enlisted in the navy as a gunnery engineer – Marine Artillery Provisional Engineer Third Class. From his military records it is evident that he served aboard the battleship “Archduke Ferdinand Max”, that he took a course for telegraphers and a naval officers course, and that he had several tours on the battleship “Radetzky”... Incidentally:“Radetzky” was in its time a remarkable ship. It was powered by twenty thousand HP engines, with a speed of twenty knots, thirteen thousand five hundred tons displacement, eight hundred and seventy six personnel, and thirty eight guns of various sizes, from three to twelve inch.

First of all to be sure, he worked as an artillery designer, and during distant voyages on warships he collected data for this work. In the evaluation of his superior officers a sentence is repeated: “...remarkably independent and remarkably gifted designer in gunnery technology.” But also: “direct, open and cheerful.” He also had good language capability. Once again from an evaluation by a senior officer: “...he speaks and reads German and Czech, speaks Serbo-Croatian and Italian well, and for official purposes adequate English and French.”

Upon termination of technical training, he received the designation “Artillery Engineer”, corresponding to an army rank of Major, and later “Chief Artillery Engineer”, corresponding to a rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

One contentious issue of the time was the battle of Czech patriots for the Czech language. In the fall of 1895 the Polish Count Kazimir Badeni was charged by order of the emperor on behalf of the new government to seek the establishment of greater recognition of the Czechs. The result of this was the language ruling of spring of 1897 for the Czech lands and Moravia, which provided for the use of Czech in all government offices, and required all civil servants to be able to function in both languages – German and Czech. This resulted in, above all, a sincere disgust among Austrian Germans – in imperial officialdom and even in the streets of Vienna.

The historian Mommsen turned to the Austrian Germans with a passionate urging to war against the Slavonic “apostles of barbarism, who are usurping the German work of many centuries to bury it in the gulf of their ignorance”. From that moment on the Czechs and the Austrian Germans stood opposed as bitter enemies in the monarchy.

In the Austrian Navy in Pola, Czechs and Germans served side by side, and when Jaroslav Hásek met an Austrian jingoist “buršák” (German student society member) they had something to discuss. Their debate over the rights of the Czech nation in the monarchy ended in a duel. Since duelling was prohibited in the armed forces, it was to be a duel “to first blood”. Jaroslav Hásek was the better swordsman. Fairly early in the match he touched his opponent lightly and with the traditional gesture presented the signal that the duel was over.

The realization that he had lost not only the argument, but also the duel to some “apostle of barbarism” was more than the loser could stand, and he swung at the unsuspecting and undefending Hásek and cut off the tip of his nose. Then one of them fainted, not the antagonist, or Hásek, both of whom were instantly covered in blood, but Hásek's second, who was a physician from somewhere in Moravia, fainted. It was probably only with the realization that he could not hide such a wound and the consequences. They would all likely be jailed. They would be discharged. The second to the “buršák”was a German doctor who rapidly and skilfully attended to Hásek. It was against the rules relating to duelling but in line with his hypocratic oath.

The incident of the duel had a later continuation in Vysoké nad Jizerou, whence Hásek set out to seek his bride, Miss Anna Brož. His nose did not look good, and when asked what had happened he said he fell down stairs. That was when his future Mother-in-law, Mrs. Magdalena Brož started to try and talk her daughter out of the forthcoming wedding. - You say that he is concerned with artillery in the force? That's possible, but he must have been really tanked when he fell down stairs and beat up his nose. You really ought to reconsider this wedding. She didn't reconsider, and she did the right thing. In the year 1900 Miss Anna Brož married Jaroslav Hásek, and she did well by it.

They spent ten years in Pola. In 1901 their son Jaroslav was born, and he died of diphtheria in 1908. In 1903 they had son Miloš, who became a lawyer, and in 1907 another son, Vladimir, later a forestry engineer, who in 1948 emigrated to Canada. (translator's note: Vladimir actually emigrated to England in 1949, and eventually to Canada in 1957.)

After departing from Pola, in the year 1914 their daughter Marie was born. Life in Pola thereafter became something of a family fable. Life in Istria was good. They lived on a hill above the town on Monte Cano. Jaroslav Hásek had work which interested him. However, he also had time for a variety of sports. He played soccer for the navy team. He rowed. He swam. He fenced. He played tennis. He also rode a bicycle of the sort we only know from old photos – a penny farthing, which must have been difficult to mount.

After departing from Pola, in the year 1914 their daughter Marie was born. Life in Pola thereafter became something of a family fable. Life in Istria was good. They lived on a hill above the town on Monte Cano. Jaroslav Hásek had work which interested him. However, he also had time for a variety of sports. He played soccer for the navy team. He rowed. He swam. He fenced. He played tennis. He also rode a bicycle of the sort we only know from old photos – a penny farthing, which must have been difficult to mount.There are a number of anecdotes from that time that Jaroslav Hásek liked to relate to his children, which his daughter Marie later documented. Perhaps a favourite was the one in which he pursuaded Madam Anna to steer his rowing four. She undertook this in a large hat of the kind ladies wore in those days. Perhaps they had artificial flowers or stuffed swallows complete with nest. It happened once on a rowing outing to the island of Brioni, that Madam Anna fell overboard and her hat floated beautifully on the surface like a small island, but Madam Anna did not swim beautifully, and sank to the bottom so that Jaroslav Hásek had to jump in and get her to the shore – and so it went.

He liked to relate how on a voyage to Japan he befriended an officer who was later Austro-Hungarian Admiral Nicholas Horthy de Nagybanya (and ultimately a long serving Prime Minister of Hungary), who gave him as a memento a short haired fox terrier bitch with the distinguished name “Miss”. It was a peace loving pooch, but when one day the mailman rapidly opened and closed an umbrella, Miss was insulted and promptly ripped his pants, and after, always whenever she saw a mailman did the same, until a letter came from the post office suggesting to Engineer Hásek that he should either get rid of Miss, or he could kindly pick up his mail himself, with kind regards, a circular seal and illegible signature.

In 1910 Jaroslav Hásek was transferred from Pola to Vienna to the Admiralty, and he was named professor of ballistics in the Naval Academy. By this time he had already implemented several inventions for changes in construction of cannons and torpedos, however I have been unable to find the details of these in the naval archives.

Perhaps still in Pola, shortly after his coming to Vienna, he had a serious injury. During a controlled firing of a cannon he was making notes at very close proximity when through carelessness a shell was fired unexepectedly and burst both of his eardrums and even damaged his inner ear. From that time on his hearing was impaired. After two years, in 1912, he applied for early retirement. He was thirty eight years old.

In Vienna he befriended Charles, Baron Škoda, the son of the founder of Škoda factories, Sir Emil Škoda. Škoda in those days manufactured principally rapid firing artillery pieces, heavy naval gun mounts, turrets and armour, terrestrial heavy artillery up to twenty-four centimetre calibre, machine guns, which were called “mitrailleuses” in those times, and munitions of all kinds. Charles, Baron Škoda, who was from 1909 owner and managing director of the outfit, was already starting to diversify – among other fields into the manufacture of locomotives, but artillery was still the most important for him. He offered Hásek employment, and the offer was accepted.

Before his entry into Škoda works, Baron Škoda sent Hásek on a six month study tour covering France, England, and the United States. The details of this have not survived. Not even a report of the results could be found in the archives of “Museum Škoda”. Members of the family by all accounts remember that as far as Hásek later spoke of the trip, it was almost exclusively about America. He reached the United States at the time of William Howard Taft's presidency, who in the same year that Hásek began to discover America for himself and for Škoda, uttered the sentence that keeps returning to modern American history until today. “Let us replace cannon balls with dollars” he said. The most important goal of American diplomacy was to be the expansion of American commerce. The same year was the beginning of unequalled development of American industry and immigration. America became the “melting pot” - according to Zangwil's stage play of the same name – in which foreign immigrants in the conditions of American civilization quickly merge with the domestic population and re-form themselves as Americans. It was not very clear what the “new American” would look like, but he would surely be different from a European.

The year 1912 was a particularly important one in American history, since it was the year that America was to become “the New World”. It is unlikely that they showed Hásek the manufacture of new American artillery, but certainly he would have learned the manner of establishment of large new factories, the first cartels. In the same year Morgan's steel cartel was already in place in America, the marine Shipping Trust, and the great American automobile industry combines that resulted in Ford, General Motors and Chrysler. It was the time of the coming of the monopolies. The large concerns were producing three quarters of industrial output, and Hásek had the unique opportunity to see close up how such companies began, how they worked and how they were managed. Undoubtedly he made the most of the opportunity.

He returned to Pilsen on the first of July 1912 and and began his employment at the Škoda works. In the same year he moved to Pilsen with his family, and a year later purchased a villa on Klatovská Avenue and began work, presumably, in the design office. Already by 1912 the Škoda factories were utilizing his patents from 1903 and 1907 for semi automatic artillery breaches, and also for “pneumatic devices” for ten centimetre, ten to twenty centimetre, and larger than twenty centimetre calibre cannon, but today no one remembers what sort of devices they were, only that Škoda started manufacture of his designs in 1912.

Overall so far there have been determined to be thirty inventions and technical patents to Hásek's credit. Their recitation to a layman is effectively meaningless. They concerned ...seals, ignition screws, arrangement of gunpowder loading, closure of cannons, mechanical and electrical detonation. He also dealt with paper cartridge casings, and still in 1938 the Ministry of National Defence ordered the first series of munitions manufactured under Hásek's patent number 55.811, but after the (German) occupation their manufacture ceased.

After the First World War he became director of the artillery division. Charles, Baron Škoda was very free with the awarding of titles. The workers at the Škoda museum have preserved a director joke to this day that is almost a hundred years old. It's already a historical monument. In a shipment from South America, a crocodile arrived at the Škoda works. It ate three directors. The incident was only discovered on payday.

Only...Hásek as director of the Artillery works was not to be overlooked, since it was the most profitable branch of the outfit. In 1923 he was named director general of Škoda and also a director of the Brno arms factory.

He was fifty years old when a year later, in 1924, he decided to change his lifestyle. Not altogether. He would never part with his drafting board. Actually, he did not even totally part company with Škoda right away, only he would now be returning as a consultant, who could come any day, but he was now “director general with half time work commitment”, so that he could concurrently be a farmer.

He bought a mansion and estate from Eisner of Eisenstein in Prčice. He became a country squire. He owned fields, fishponds and forests, only he did not yet know how to manage them. Naturally he employed managers, in aquaculture and forestry, who had the knowledge, and he learned quickly. That capability stayed with him, even when the subject matter changed.

He bought a mansion and estate from Eisner of Eisenstein in Prčice. He became a country squire. He owned fields, fishponds and forests, only he did not yet know how to manage them. Naturally he employed managers, in aquaculture and forestry, who had the knowledge, and he learned quickly. That capability stayed with him, even when the subject matter changed.Of working fields he retained only fading memories from childhood – their small and poor holdings had become, over time, ever smaller – but all the same, he quickly began making his own decisions in the running of Prčice. Before doing that, though, he was able to listen to good advice. Early on he adopted the habits of a farmer. In the early morning he would go around his fields and observe how low green stems changed to green seas and before the harvest he learned how to rub the ears of grain in his fingers and count the seeds,...and so on. He entered a different world. Soon he felt comfortable and safe there. And he also applied his knowledge and technical skills to improve estate management.

He used to return to Škoda and several of their operations scattered across the republic. He represented Škoda in negotiations likely all across Europe, and certainly in all the states with which Škoda had business.

He was also still a military man. The Czechoslovak Republic took over responsibility from the defunct monarchy to its officer corps, and enlisted Hásek in the roll of senior officers of the militia command in Prague with the rank of Lieutnenant Colonel. In 1931 he had the right to receive Kcs25,800 as a retirement settlement, but since he informed the Ministry of Defence that he had other income of Kcs150,000 in the same year, his “provisional” payout was adjusted to Kcs7,327.20. Only in 1938, when the second world war was on the verge of erupting did he part company with Škoda for good.

Later he lived only in Prčice.

He walked in the fields, to the ponds and in the forests of Czech Merán (name of region). He always had a dog who went with him. According to some accounts it was always some doggie who had his engineer Jaroslav Hásek along, who could not have asked for more.

He walked in the fields, to the ponds and in the forests of Czech Merán (name of region). He always had a dog who went with him. According to some accounts it was always some doggie who had his engineer Jaroslav Hásek along, who could not have asked for more.Finally, he was able to read books, for which he had not had time all his life. Czech historical novels in Czech, German novels in German, and he “dusted off” his English with whodunnits. Gradually he accumulated a large and unique collection. He also became a mycologist, and because whatever he took up he did thoroughly, likely when he brought home brown edible mushrooms from the local woods he would refer to them as Xerocomus badius. As a memory of Istria and hot climate whence he sailed on Austrian naval vessels, he built a greenhouse where he cultivated figs, citrus and artichokes...

He was almost eighty years old when he still managed to swim across Kammeny pond, and he was already an old man when once in winter he came across a frozen pond where a group of boys and girls were skating. He borrowed a pair of skates and demonstrated a perfect jump. Then he tried a whole series of jumps, only one of them failed – it was the exception that proved the rule – since his jumps really were perfect, and he managed to sustain a concussion. He played tennis, He didn't cease his hiking the trails of Czech Merán. However they were not the leisurely strolls of an old man looking after his health, they were almost route marches, even though the time for for route marches was at the time still distant.

After February 1948 the mansion and estate at Prčice were confiscated by the state. Among the justifications for the action was that he did not need any of it, since he had a good pension as the retired director of Škoda works. In 1953 they also seized his good pension with the rationale that he used to own the mansion and the estate and therefore had enjoyed elevated status. On the 18th of May, 1953 the board of the regional council in Sedlcany announced to Jaroslav Hásek that under some paragraph of some government regulation it had come to their attention that it was necessary to reduce his pension from Kcs 5,878.00, which he had been receiving up to that point, to Kcs1,000.00 per month. Incidentally, this was in the old currency, i.e. Kcs200.00 new currency. The reason? “...in the time of the exploiting regime you had particularly high standing in society and you were a notable supporter of the earlier political and economic system.”

In a letter which Jaroslav Hásek sent on June 10th 1953 to the appeal commission of the state bureau of income assurance in Prague he wrote: “...only with difficulty did I complete the work to achieve advanced technical education... The cause of my advancement was soully honest professional and technical work. As a designer I have had patented a series of inventions, the protection of which has in the meantime expired, but which in their time represented a substantial value added to Czechoslovak manufacture and technology... Regardless of the fate of my inventions currently – I myself no longer have insight to the nature of the industry and cannot know it – they represented technical advancement. They form part of the foundation of technical developments of today's generation. They have value even today, and it is inconceiveable to me that a Czech engineer, designer is today – regardless of having no assets or income – in his eightieth year deprived of his old age pension. I am convinced it must be a mistake... I acquired my property and my status not as an objective of my labours, but as a result. The work and its outcome interested me in the first instance, and were my own life... I am almost eighty years old, I live in the country with my seriously ailing wife – who has been unable to leave her room for a year – and with a sixty-nine year old ex-servant who has been with me for over forty years, has grown to be a member of the family and wishes to share in my fate... and I am now losing my pension, and I do not know how I shall manage to survive these last few years remaining to me.”

I do not know if anyone answered the complaint. If it was done, it would likely have been advice that there is no reason for the decision of the regional council in Sedlcany to be altered.

Shortly after February 1948 Jaroslav Hásek had to vacate the mansion and leave all former furnishings and artworks behind.

He was given a flat in the “new estate office”, on the upper floor of the house which stands in the right angle bend of the road to Sedlec, where there is once more an estate office, only no longer “new” by a long shot.

He was given a flat in the “new estate office”, on the upper floor of the house which stands in the right angle bend of the road to Sedlec, where there is once more an estate office, only no longer “new” by a long shot.From the original five rooms they progressively cut portions, until there were only three left. On the ground floor there were police, who were known at that time as: “members of the committee responsible for national security”.

He was allowed to take his drafting board with him. Almost all his life he had been returning to it. He did this right to his final days. He needed to sit in front of it, from early morning and precisely until noon, having at hand his drafting pens and india ink, long rule, square, compass, sharpened pencils, drafting paper and thumbtacks to attach the drafting paper to the board. Then he also had a slide rule, and that was about all.

Almost all his life he was first of all a designer and inventor. He did not cease to be that even in the “new estate office”. George Kofron, who used to visit him there still as a student, remembers to this day the when he rang the doorbell outside a widow upstairs opened, engineer Hásek looked out, pulled on a string which lead via a series of pulleys and levers to the front door latch, and the door opened before him. At this time engineer Hásek worked over his drafting board on the resolution of his last great invention. He likely did not pay heed to how his world had changed, though he may have felt that he always lived under heavy leaden clouds, but he would not have searched for metaphors, only technical solutions to his tasks. He tried to imagine a cannon – and first of all design such a device – for the dispersal of clouds. He was unable to complete his last invention. Drawings, notes and calculations from this time were not perserved. Engineer Jaroslav Hásek died in 1954.

References:

Recollections of Mrs. Marie Janota, daughter of engineer Jaroslav Hásek

Archives of Mrs Alena Sourek, granddaughter of engineer Jaroslav Hásek

Archives of the Military Museum in Prague

Archives of the National Museum in Prague

Archives of Škoda Museum in Pilsen

Masaryk's Encyclopedia, 1933

Die Schiffe der k.u.k. Kriegsmarine im Bild, Vienna, 1999

Record of the Third Congress of all Sokol, Prague, 1895

Jan Navratil: Brief History USA, 1995

Kamil Krofta: Czechoslovak History, Prague, 1946